Despite having 30+ slides of economic/market research and no shortage of content to share with you this month, after having written the majority of my monthly commentary, I have decided that it would actually be more valuable to turn this commentary over to my favorite analyst, Porter Stansberry.

As long-time readers and clients likely know, Porter was an inspiration for me enrolling in the CFA Program many years ago. I have learned more about how to make (and perhaps more importantly, how to protect) money in markets from him and his companies over the years than I did from earning my CFA Charter. That isn’t to disparage the CFA Charter either - it’s just the truth.

Also, as I think most of you know, I remain bearish despite the seemingly “resilient market” we have seen in 2023 (which is really just 7 stocks going up).

The content below can be found here, on the Porter & Co. website. It’s free.

Full disclosure, there is a sales pitch at the end to subscribe to their paid content which is geared mostly for folks who want to manage their own portfolios. We have no affiliation with Porter & Co. and have no financial interest if you decide to pay them.

I will come back at the end to wrap up and share a few charts and slides with commentary. But for now, enjoy a little history lesson!

The Three-Year Lag the Fed Always Forgets

November 3, 2023 | Porter & Co.

When the Fed aggressively hikes rates, it often ends up triggering a crisis of the very kind that it hopes to prevent. And seemingly, central bankers haven’t learned their lesson this time, either…

Instead of Being Patient, It Aggressively Tinkers

Harry probably shouldn’t have left his friend Eddie alone to mind the store.

The two buddies split duties at their Missouri haberdashery “equally” – which in practice meant that Eddie stayed behind the counter and hawked shirts and “no-wilt” collars, while Harry gallivanted around town under the guise of business lunches.

Then the Depression hit – and Harry likely wished he’d paid a little more attention to what went on behind the counter.

“A flourishing business was carried on for about a year and a half,” he wrote later, “and then came the squeeze… [Eddie] Jacobson and I went to bed one night with a $35,000 inventory and awoke the next day with a $25,000 shrinkage…. This brought bills payable and bank notes due at such a rapid rate we went out of business.”

Harry and Eddie had to liquidate and file for bankruptcy – and they weren’t alone. The stock market crashed, business failures tripled, and company profits on average fell by around 75%. As prices plunged, employment ticked up toward 12% and more than a thousand banks closed their doors.

Oh, and here’s the kicker – this wasn’t even the Great Depression.

This was a severe, 18-month economic contraction – from January 1920 to July 1921 – that’s largely ignored in history books. When it’s mentioned (rarely), it’s called the “Forgotten Depression.”

It all started during the post–World War I boom. At that time, the U.S. was still on the gold standard – each U.S. dollar was backed by a corresponding amount of the precious metal. There was a post-war surge in spending to rebuild the neglected country after so much had been spent overseas to support the troops. The resultant increase in the money supply and in consumer prices caused a massive drain on the country’s gold reserves.

To cool down the economy and slow the loss of gold, the Federal Reserve began to raise interest rates aggressively. It hiked rates from a low of 3.5% in 1917 to a then-record-high 7% by early 1920.

The Fed’s first big rate-hike cycle (the central bank had only been founded in 1913) took several months to weigh on the economy. But once it did, the consequences were dramatic. The Dow Jones Industrial Average fell by nearly 50%, and the U.S. suffered its sharpest drop in wholesale prices in history (worse than even the Great Depression that followed a decade later).

The adolescent Fed didn’t immediately cut interest rates in response to this crisis. Following the guidance of Benjamin Strong – head of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York – the Fed instead held rates at these high levels for the better part of a year as the crisis played out.

Strong believed in the self-correcting nature of markets (that is, in the Invisible Hand). He figured that the only lasting solution to the post-war boom was a commensurate bust – and he was convinced the crisis would resolve most quickly without government interference. As he predicted in an early 1919 letter to his friend, economist Edwin W. Kemmerer…

“I believe that this period will be accompanied by a considerable degree of unemployment, but not for very long, and that after a year or two of discomfort, some losses, some disorders caused by unemployment, we will emerge with an almost invincible banking position, with prices more nearly at competitive levels with other nations, and be able to exercise a wide and important influence in restoring the world to normal and livable conditions.”

Strong was uncannily correct… right down to the “year or two of discomfort.” The Forgotten Depression ran its course in less than two years. And by 1922, the economy had fully recovered. As legendary financial newsletter writer Jim Grant – author of the definitive book on this crisis – noted in the Wall Street Journal in 2015:

“In the absence of anything resembling government stimulus, a modern economist may wonder how the depression of 1920-21 ever ended. Oddly enough, deflation turned out to be a tonic.

“Of course, the year-and-a-half depression must have seemed interminable for all who were jobless or destitute. It was, however, a great deal shorter than the 43 months of the Great Depression of 1929-33. Then too, the 1922 recovery would bring tears of envy to today’s central bankers and policymakers: Passenger-car production shot up by 63%, for instance, and the Dow jumped by 21.5%. ‘From practically all angles,’ this newspaper judged in a New Year’s Day 1923 retrospective, ‘1922 can be recorded as the renaissance of prosperity.’”

Prosperity returned a bit too late for young Harry, who lost his haberdashery in the bust. But, as his cousin Mary acknowledged, no one who knew him was surprised he went bankrupt.

“Well, we of course were sorry that he didn’t make a go of it,” she said years later in an article about her cousin, “but we couldn’t feel that that was Harry’s life work any more than farming had been, and I think we just took it without too much concern, because we all felt that he hadn’t gotten into the thing that would bring out the best that was in him.”

Not to worry, though – Harry eventually found his niche. A couple of decades after the Truman & Jacobson men’s clothing store closed its doors, Harry S. Truman became the 33rd president of the United States.

Selective Amnesia

The Forgotten Depression carried several critical lessons for central bankers.

It illustrated that busts are a natural and necessary consequence of booms – while painful, they’re essential for liquidating bad debts and malinvestment and for “resetting” the system.

It showed that these crises can resolve themselves quickly without government interference.

And it highlighted that monetary policy acts with a significant lag. Specifically, the effects of rising interest rates don’t begin to show up in the economy until two to three years after tightening begins, regardless of how aggressive central bankers act.

The lag likely has to do with the term structure of debt – most borrowers typically don’t have to refinance at higher rates immediately. Plus, even the weakest borrowers often have some amount of equity or savings they can rely on initially. But regardless of the reasons, these delayed effects have proven to be remarkably consistent over time.

Unfortunately, like the Depression of 1920-21 itself, these lessons were quickly forgotten, if they were ever learned at all. (It doesn’t help that the University of Chicago’s Center for Research on Security Prices database – the source for most historical stock market and financial information today – only goes back to December 1925.)

In virtually every boom since, the Fed has sought to avoid busts at all costs. It has typically intervened aggressively to stop them at the first signs of significant trouble in the markets or the economy. And though Fed officials often give lip-service to Milton Friedman’s 1959 insight about the “long and variable lag of monetary policy,” their dogged impatience over the past 100 years suggests they’ve yet to take this enduring lesson to heart.

Delayed Crises Are the Rule… Almost Without Exception

A look at financial history since the 1920s shows this lag between rising rates and their inevitable economic and financial consequences is not just remarkably consistent, it’s also typically longer than just about anyone – including those controlling the levers at the Fed – expects in real time.

This unfortunate reality has led to a predictable yet recurring problem. As you can see in the chart below, when the Fed aggressively hikes rates, it often ends up triggering a crisis of the very kind that it hopes to prevent.

SOURCE: Porter & Co.

This dismal pattern began a few years after the Forgotten Depression. As a new speculative boom took hold during the second half of the decade, the Fed started raising rates sharply in early 1928, ultimately reaching a peak of 6% in 1929.

But it wasn’t until October 1929 – roughly two years from the start of that tightening cycle – that the stock market began its historic plunge (the Dow would go on to drop 89% before bottoming in 1932). And it was still another year after that before the Great Depression went global in early 1931. That’s when Austrian bank Creditanstalt – one of the largest and most important banks in Europe – collapsed, setting off a deflationary crisis that quickly spread across the continent.

The 1960s and ‘70s saw this cycle repeat several times.

In mid-1967, in an effort to fight inflation, Fed chair William Martin began an aggressive tightening cycle. In just over two years, he more than doubled the fed funds rate from 3.75% to nearly 10%.

Yet, it still took another 10 months – and three years in total – before trouble began. Economic shockwaves followed the failure of railroad giant Penn Central, at the time the largest corporate bankruptcy in history. Since the railroad controlled a third of the nation’s passenger trains and a majority of freight traffic in the Northeast, its collapse created significant economic and financial market fallout.

In addition to the obvious disruption of interstate trade and significant losses among the company’s many pensioners, the collapse triggered a liquidity crisis in the short-term corporate-debt market that nearly bankrupted renowned investment bank Goldman Sachs.

And Still No Lesson Learned

Martin’s successor – the much-maligned Arthur Burns – presided over a similar tightening cycle a few years later.

Despite his legacy of being “soft” on inflation, the Burns Fed aggressively raised rates from less than 4% in early 1972 to a whopping 13% in July 1974. And it was not until October 1974 – nearly three years into the tightening cycle – that his Fed finally relented.

In that cycle, the central bankers feared the recent collapse of Franklin National Bank, the largest bank failure in U.S. history at that time, could trigger a financial crisis (much like the failure of Lehman Brothers several decades later).

Regulators quickly stepped in – orchestrating the first federal wind down of a major financial institution in history – and Burns cut rates back down to 5% to ease financial conditions, even as inflation remained high.

Even famed inflation-fighter Paul Volcker was a victim of this lag.

As many recall, Volcker held rates as high and as long as necessary to defeat inflation – rapidly pumping up the fed funds rate above 20% by 1981.

But when Volcker finally gave up his fight in 1984 – again, roughly three years after his final tightening cycle began – it was not because inflation had been defeated. Consumer prices would continue to rise between 4% and 6% annually – well above the Fed’s target – for much of the next decade.

Rather, Volcker began cutting rates following the near-failure of Continental Illinois National Bank – the country’s largest commercial and industrial lender and arguably the first “too big to fail” bank – that threatened to trigger a financial crisis that spring.

Most notably, Volcker’s successor, Alan Greenspan, played a role in multiple such cycles in the following decades. Those lags culminated in the “Black Monday” stock market crash in October 1987, the savings-and-loan crisis in the early 1990s, the dot-com boom and bust in the late 1990s, and ultimately, the 2000s housing bubble and the Great Financial Crisis that followed.

And despite all that history could have taught him, former Fed Chair Ben Bernanke – who took over the reins from Greenspan in 2006 – was most famously fooled by the lag.

In a speech in March 2007 – almost three years after the start of the Fed’s most recent rate hike cycle – Bernanke assured Congress that the growing problems in the subprime mortgage market were “contained” and unlikely to impact the “broader economy and financial markets.”

Of course, we now know that the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression was already brewing, and the Fed would begin cutting rates in a panic just a few months later.

Bernanke’s misplaced confidence is among the biggest blunders in modern financial-market history. But as we’ve seen, virtually every Fed chair – along with most investors and market pundits – has made similar mistakes in every tightening cycle in U.S. history.

The “End Game” Is Clear

That brings us to where we are now.

You’ve likely read or heard commentary about the “surprising” resilience of the U.S. economy in recent months.

Over the past year and a half, the Jerome Powell-led Fed has raised short-term rates from near 0% to 5.5% – representing the most aggressive tightening cycle in history on a percentage basis.

Yet, despite total U.S. debt levels – including federal, corporate, and consumer debt – being roughly double what they were in 2007, these recent rate increases haven’t created any severe problems in the U.S. to date (outside of a handful of regional bank failures).

The lack of any significant fallout from the Fed’s aggressive hikes – so far – has led many investors to assume that “this time” really is different… That these moves will somehow successfully tame inflation without causing a financial crisis.

Unfortunately, today’s cheerleaders are likely to be disappointed, like countless others before them.

Despite growing optimism that the Fed will achieve a “soft landing,” more than 100 years of history suggests a crisis is unavoidable. And we’re now approaching the period in the cycle – roughly two years after the first rate hike – when it is most likely to begin.

SOURCE: Porter & Co.

We’ve already witnessed significant stress in the banking system – though there will likely be more disruptions ahead. And we’re just beginning to see signs that the economy is teetering, including a slowdown in housing, manufacturing, and corporate profits, rising consumer delinquencies, and weakness in commercial real estate. It’s likely just a matter of time before another crisis begins.

But the delayed consequences of Fed policy isn’t the only predictable aspect of these cycles.

In each of these prior scenarios since the Great Depression, the Fed also aggressively reversed its policy as panic set in. And as these crises have become increasingly more severe under the growing pile of bad debts and malinvestment over the years, the Fed’s responses have also grown larger and more dramatic – flooding the economy with more liquidity and stimulus each time.

This trend suggests the next crisis – the “End of America,” as we’ve called it – will be one for the record books… And the Fed’s response to it will be among the biggest and most inflationary in history. Unfathomable amounts of money-printing are assured.

Here at Porter & Co., we believe the surest way for investors to protect – and even build – wealth in the years ahead is to own hard assets (particularly gold and Bitcoin) and the world’s most dominant, capital efficient businesses.

However, it’s also important to understand that the Fed historically acts only after a crisis is already underway.

In the meantime, we could experience severe economic and market turmoil, including soaring unemployment and unprecedented market volatility. Investors who take on too much risk – even in the highest-quality equities – may be unable to weather the storm.

This is why we continue to urge investors to remain patient and conservative. The coming crisis will present a once-in-a-generation wealth-building opportunity to buy the best companies at bargain-basement prices – but only for investors who have the capital available to take advantage.

And rest assured, our paid-up The Big Secret on Wall Street subscribers can count on us to tell them exactly when this opportunity arrives. If you’d like to join them, click here to get started now.

Porter & Co.

Stevenson, MD

P.S. If you’d like to learn more about the Porter & Co. team – all of whom are real humans, and many of whom have X accounts (formerly Twitter) – you can get acquainted with us here. You can follow me (Porter) here: @porterstansb.

Well, hopefully you can see why I thought this would be a valuable read for you and I hope you got something out of it. One other thing you might want to check out to get even more insight is Porter & Co.’s free monthly podcast. You can find that here, or wherever you listen to podcasts.

But consider yourself warned: if you do decided to tune in, it probably contains some language and perhaps some political views that you may not want to hear.

Before I get to some charts/slides, I want to call your attention to a new section of our website where you can find detailed information on the different strategies we offer at Elevate. You will likely notice some different names for the strategies.

Going forward, what I used to call the “Growth” strategy will be known as “The Elevate Capital Strategy” and what I used to call the “Value” strategy will be called “The Elevate Capital Low-Volatility Strategy.” Not much else will change. The words “growth” and “value” were just too loaded and seemingly restrictive. The growth strategy was never limited to only growth stocks, nor was the value strategy limited to only value stocks… So, for me, the names just didn’t fit. At the same time, as a portfolio manager, I wanted to take the opportunity now to re-focus on what I believe is most important for building a long-term portfolio of investments.

Writing helps me to stay focused on those important things. As Warren Buffet said:

I taught my first investing class 70 years ago. Since then, I have enjoyed working almost every year with students of all ages, finally “retiring” from that pursuit in 2018.

Along the way, my toughest audience was my grandson’s fifth-grade class. The 11-year-olds were squirming in their seats and giving me blank stares until I mentioned Coca-Cola and its famous secret formula. Instantly, every hand went up, and I learned that “secrets” are catnip to kids.

Teaching, like writing, has helped me develop and clarify my own thoughts. Charlie (Munger) calls this phenomenon the orangutan effect: If you sit down with an orangutan and carefully explain to it one of your cherished ideas, you may leave behind a puzzled primate, but will yourself exit thinking more clearly.

With that, lets jump into a few quick charts that I feel need to be shared, before I sign off.

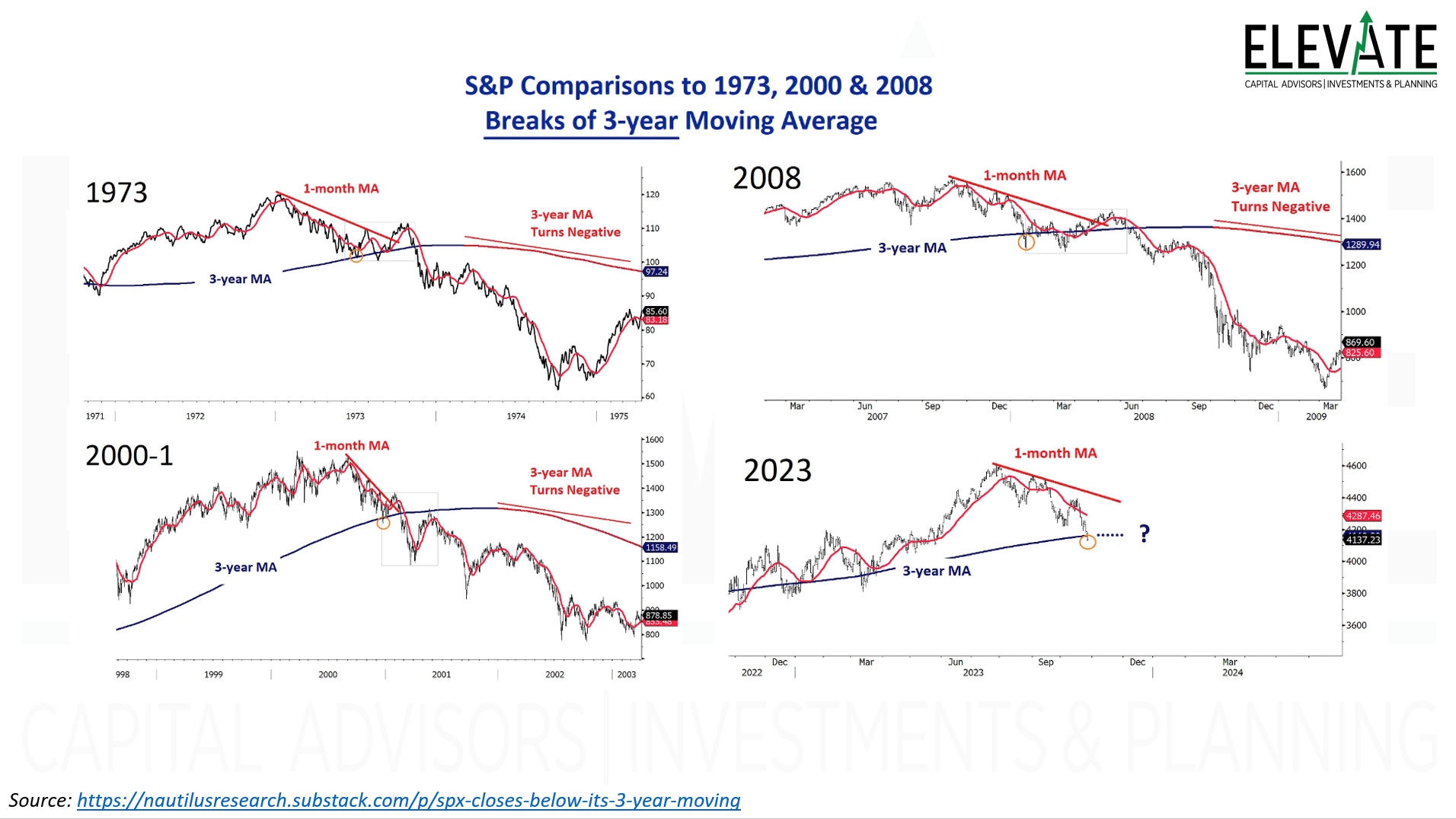

3-year Moving Average

As you can see in this chart, there have been at least a few times when the S&P 500 dropped below its 3-year moving average and that was just the beginning… with much bigger losses to follow. We just hit that level.

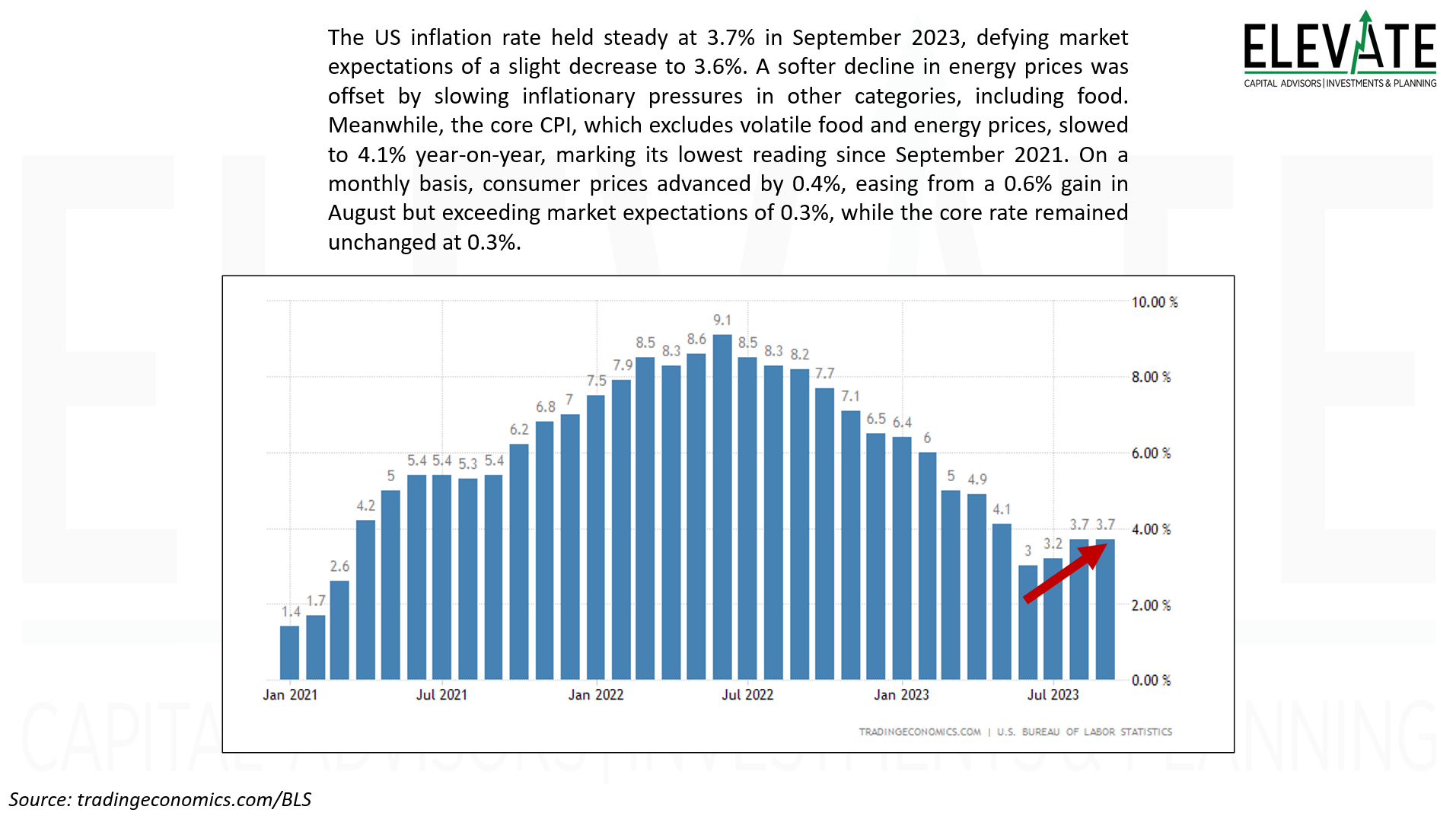

Inflation isn’t falling…

Inflation (CPI) was reported last month at 3.7% for the second month in a row. Sure, 3.7% is better than 9%, but it is also almost double the 2% target. And as the next image comically asserts, 3.7% in October 2023 on top of 8.2% in October of 2022 is a compounded rate of 12.20% over the past two years.

Hedgeye

They do great cartoons… in light of the above slide/data, you should get the joke!

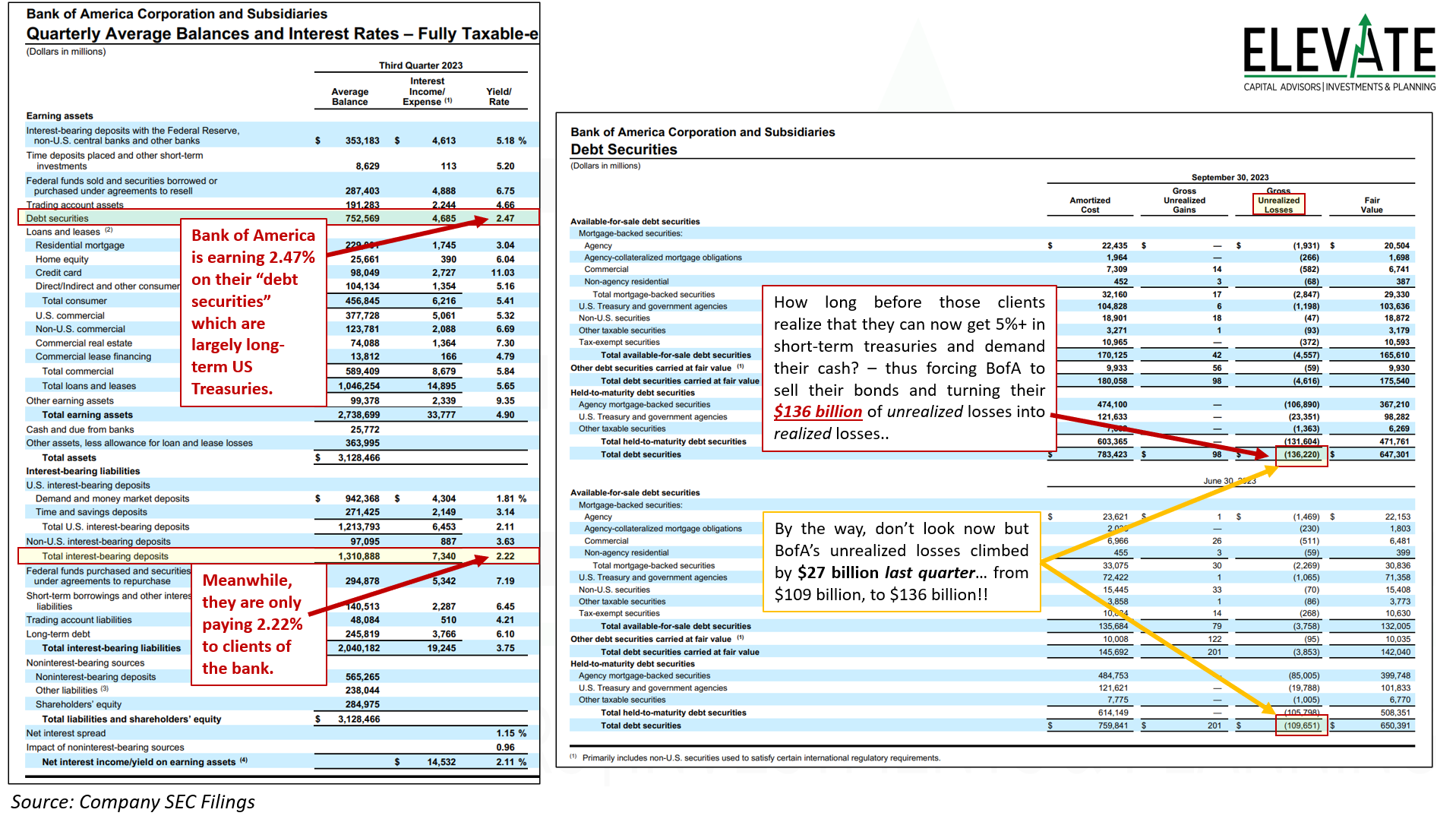

Bank of America

What the slide fails to highlight is that the $26 billion of unrealized losses last quarter are a direct function of the long-term US Treasuries that the bank owns have yields so low (2% or less in many cases) that as current rates go higher and stay there - the market value of these long-term bonds with low yields drops fast. What is crazy is that these losses don’t stem from risky loans or crypto banking, rather they stem from the safest investment on earth - US Treasury Bonds. And pretty much every bank on earth has this same problem. For now, those losses are unrealized… but if the bank is forced to sell those bonds at a loss to pay back clients who take their money out it would be a big problem.

Change in Bank Deposits

Again with reference to the above slide, you can see that the banking industry has lost deposits at a rate we have never seen before. Many people (like our clients) are opting to pull money from their banks and buy short-term US Treasuries at very high yields of 5%+.

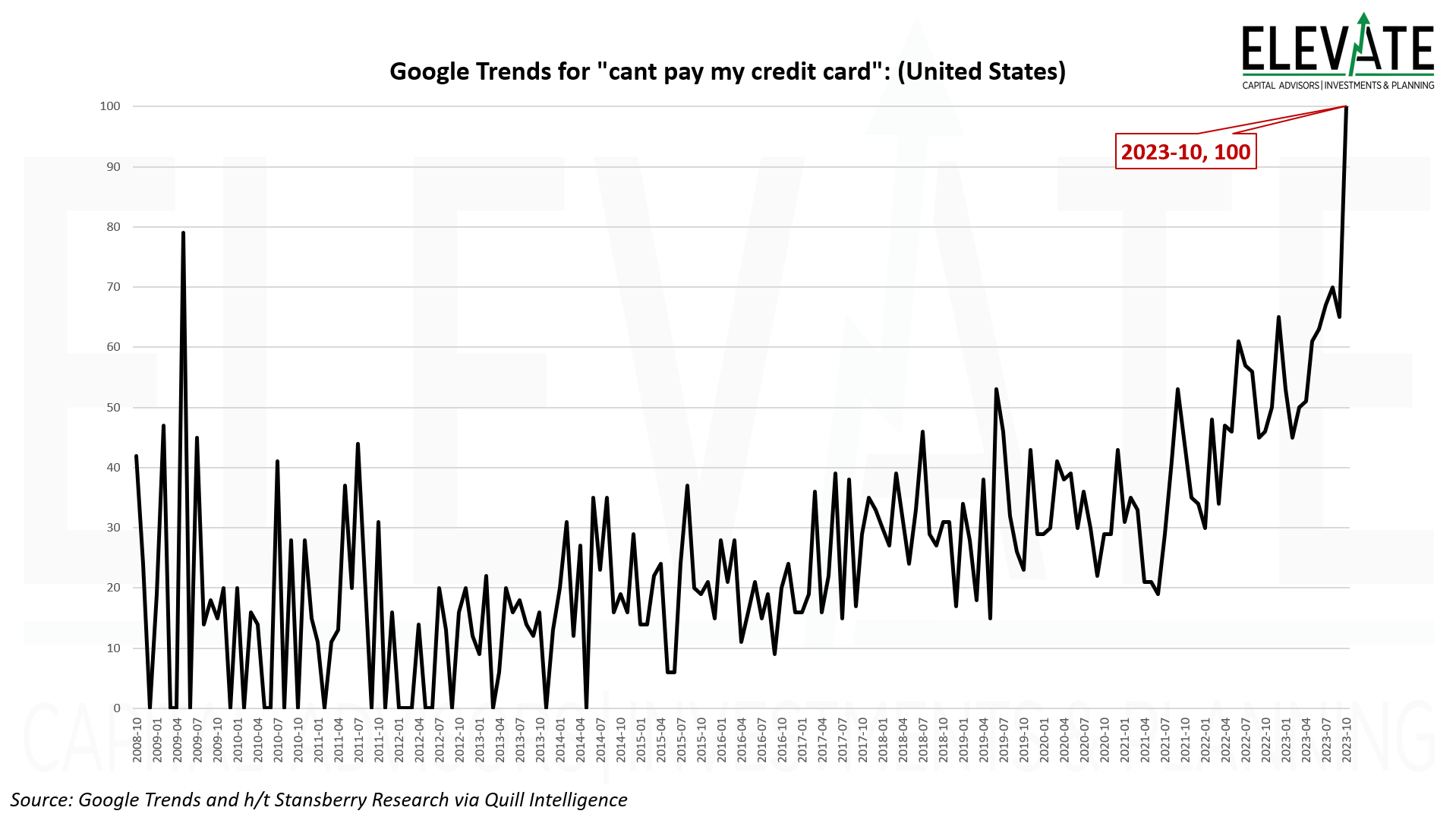

“ I can’t pay my credit card”

Google Trends is really cool. Check it out if you never have. People are searching the term “I can’t pay my credit card” at a higher rate than ever before - including during the Great Financial Crisis of 2008-09. Sure, there were fewer people using google then, but still.. is it any surprise that coincides with student loan payments being reinstated?

Until next time, I thank God for each of you, and I thank each of you for reading this commentary.

Clients, I encourage you to click here to access your personalized performance portal to see how your portfolio performed vs. the markets last month.

Shane Fleury, CFA

Chief Investment Officer

Elevate Capital Advisors

Legal Information and Disclosures

This commentary expresses the views of the author as of the date indicated and such views are subject to change without notice. Elevate Capital Advisors, LLC (“Elevate”) has no duty or obligation to update the information contained herein. This information is being made available for educational purposes only. Certain information contained herein concerning economic trends and performance is based on or derived from information provided by independent third-party sources. Elevate believes that the sources from which such information has been obtained are reliable; however, it cannot guarantee the accuracy of such information and has not independently verified the accuracy or completeness of such information or the assumptions on which such information is based. This memorandum, including the information contained herein, may not be copied, reproduced, republished, or posted in whole or in part, in any form without the prior written consent of Elevate. Further, wherever there exists the potential for profit there is also the risk of loss.